Day 98, Wednesday, June 12, 2024: Marion, Indiana to Rochester, Indiana

- Mark Carl Rom

- Jun 30, 2025

- 9 min read

Carnegie libraries visited: Flora, Delphi, Monon, Royal Center, and Kewanna, Indiana

Days sober: 356

When the Board of Trustees of the Flora Public Library approached Carnegie in January 1903 seeking funds, it claimed that “The people of Flora are progressive, enterprising, and intelligent” and the town was “rapidly growing in wealth, population, and influence.” Yet danger lurked: “each evening a large number of employees are turned out to seek recreation, and finding no other place open, drift into saloons and like places, where good character and good habits are lost, and never found.” James Bertram, Carnegie’s personal secretary, was persuaded and in just the next month offered the town $10,000. By 1906, Bertram was scolding the town, writing that “Carnegie is not paying for Grand Pianos [and] beautifying parks…” For whatever reason – Carnegie’s archives are silent on this point – the library was not completed until 1918.

Like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates, you never know exactly what you’re going to get when you open up a library. In the Flora Public Library, I met Kim, then Cathy, then Rachel, the Head Librarian. Kim, in her short red hair, black glasses, lime “Pull Together Now” t-shirt with a graphic of two boys blowing bubble gum while pulling a cart of books, turquoise shorts, and Birkenstocks was my most enthusiastic library guide. I wasn’t planning to work at this library – I came in mainly to write Father’s Day and birthday cards – until I sat next to a room as small as a phone booth labeled “The Martha Hoffman Room: Director 1956-1988.” And so

I approached the front desk, and Kim, asking “What do you know about Martha?”

Lots. Kim took me to the window and pointed to a tidy yellow house just down the way at 308 North Center Street. “That’s where I grew up. A train depot was just behind my house, and sometimes kids hopped off the train and into my yard looking for playmates. Mrs. Hoffman lived a few houses down, and I used to bring those kids along to play with her grandkids.” Hoffman was the Head Librarian when Kim was a child. Kim was and is a bibliophile. The children’s section of the library was much smaller back then, and after Kim had exhausted the children’s catalogue Hoffman took her up and introduced her to the books in the main stacks. I share a similar powerful memory with her.

I followed Kim as she led me downstairs to a poster which provided details of the individuals most important to Flora’s history. I snapped a few pictures of it until Kim said “Do you want to see the cave I made?” She had draped a small hallway in black fabric and hung red glow lights. A stuffed tiger sat poised to leap from a shelf. The tiger, she explained, was to be part of a jungle scene, until she changed her mind and built the cave while keeping the tiger. The walls in the next room covered floor to ceiling with plastic sheets with various themes (mermaids, forests, clouds). Kim said “I like to decorate. The trick is to use clean remove painter’s tape and a hot glue gun.” The tour concluded with a lengthy monologue about the ghosts that inhabit the library. She reported that several librarians had seen and heard them, so one day they brought a priest over before the opening hour to wave some incense and pray the ghosts away.

Martha Eikenberry Hoffman (1920 - 2009), born in Flora, married DeVere “Pete” Hoffman and, based on his biography in a poster on the library’s walls, Pete never slept; he was a leading member of seven clubs, one of the founders of the town’s Little League, and he coached American Legion baseball, in addition to his job as an office manager and role as Clerk-Treasurer for the town.

Martha was not exactly sitting on her hands while Pete was off Peteing. In addition to raising her sons (Mike, Darrell, and Greg), she was active in many local organizations and served as a director-at-large for the Indiana State Library Board. As the Director of the Flora library, she made numerous improvements to it during her record-setting thirty two years of service there. Some of the changes might seem minor, as when she installed a “modern” hanging file system so that patrons could easily find the most recent issues of a magazine as well as previous ones. She converted the community room on the lower level to The Maude Ayres Children's Room in 1978, leaving more room for the adult collection upstairs. (Ayres died after her husband and, having no heirs, she gave her estate to the libraries in Flora and Delphi as well as to the Indiana Baptist Homes and Hospitals.) She recorded all the stories for her library’s “Dial A Story” service in 1980, which received over 2000 calls a month. Her summer reading program activities informed and entertained generations of the town’s children. After she retired, she worked with children at Carroll Elementary School to improve their reading skills and also advocated on behalf of senior citizens.

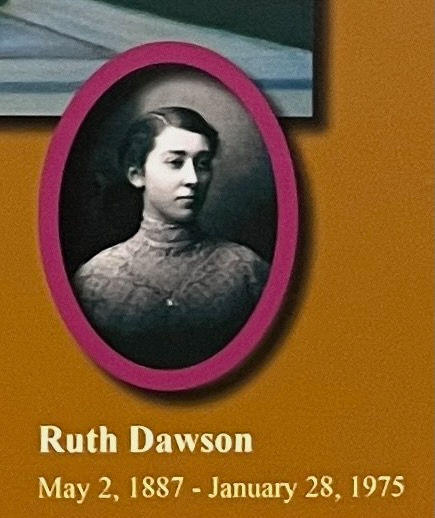

Hoffman was not the first person to lead Flora’s library; Miss Ruth Dawson (1887 - 1975) was when the library opened (apparently, without fanfare) in 1918, at the salary of $35 per month. Dawson was a graduate of Depauw University, where for her graduation picture she chose the quote “I’ll be led by no man,” and the University of Illinois Library School. The year after becoming Director, Dawson requested a telephone; the library board bought her a typewriter instead. She didn’t get a phone for ten more years. In 1924 she did get a raise, of sorts: she was given the job as the library’s janitor for an additional $260 annually. In 1940, after twenty two years on the job, she was given a well-deserved one-week vacation. Rested and ready, Dawson served another seven years, with no other vacations noted in the record. She was invited to attend the library’s 50th anniversary celebration, some twenty years after she retired, but she begged off: “I was 31 when the library opened and aching to put some of my library knowledge to work. I had come to Flora without a hint that you were launching a new library and it fell right into my lap. I have pleasant memories of the years I spent there.”

Other women important to the Flora library include Mary B. Parks (1920 - 2011), who left a “substantial bequest” to it; Edith V. Cook (1897 - 1981), who worked as a telephone operator in Flora for 43 years, and whose brother Arthur created a memorial fund in her name to purchase inspirational fiction (the books are labeled COOK on their spines); Eleanor Alice Raff Carter (1921 - 2014), who served as the library’s director in the one-year gap between Dawson and Hoffman; Kathern Creek Shope (1907 - 1994), who as a student wrote a paper on the library’s early operations and later became its director for the eight years after Hoffman stepped down.

The Flora Public Library – like any and every public library – can inspire those who walk through its doors. Minnie-Lou Chittick Lynch (1916 - 2008), was a Flora native whose love affair with libraries began when she was only four (Ruth Dawson would have been her librarian) and first using the town’s library. She worked as a shelver there during high school and, as she remembered, most of her paycheck went towards overdue fines. Later on, when she and her husband moved to Oakdale, Louisiana, she was appalled to find that there were no libraries within 40 miles and so she set up establishing one, what is now the Allen Parish Library (she served on its board for 51 years). Libraries became her life’s work. Minnie-Lou was selected as the national president of the American Library Trustee Association and a delegate to the International Federation of Library Associations at The Hague, Netherlands. She wrote articles for professional journals and gave speeches on library affairs in 35 states. She has been named one of the Extraordinary Library Advocates of the 20th Century by the American Library Association. The tribute to her on the walls of the Flora library states that “had it not been for the Flora library, the impetus [for Minnie-Lou’s career] would not have been present and her life would have been very different and less joyful.”

The library board’s 1903 opinion that Flora’s “wealth, population, and influence” were growing rapidly did not pan out. The town’s population had indeed nearly doubled, from 639 in 1890 to 1209 in 1900, although it didn’t exceed 2000 residents until 1980 and has been slowly shrinking since then. That the townsfolk were “progressive, enterprising, and intelligent” does seem to be accurate. In addition to the women noted above, Flora was also the birthplace of Paul S. Dunkin (1905-75), who by the end of his career was named as one of the 100 most leaders of library science in the 20th century. A modest town with two of the most important library leaders of the 20th century? That’s Flora.

While I was snapping a few shots of the Delphi Carnegie, a deeply tanned man and his granddaughter got out of their car in front of me. Without prompting, he began talking: “That’s a Carnegie Library.” He then launched into a brief story about Carnegie libraries, about his daughter going swimming AND to the library, and, after seeing Goldfinger, his twenty seven years as a quality control employee of Subaru. Midway through, he said “My wife thinks that sometimes I talk too much.” I agreed that Carnegie libraries were indeed beautiful.

In my eight days in Indiana, I’m visiting some forty Carnegie libraries, still only a fraction of the 164 public libraries Andrew funded here. I have a tabletop sized US map and have been using a Sharpie to trace my route. Until Indiana, the line I drew was a continuous loop, with the only place touched more than once being Fayetteville. In Indiana, I’ll be drawing the scrawl of an angry kid with a pencil, as there is little rhyme and less reason in my route. Given how many libraries there are here, there was no easy way to plan my itinerary. I typically picked a town, and then used Google maps to find another town close to it, so that I could continue my “never backtrack” pledge as closely as possible. With nearly one hundred libraries still open to the public, it was too difficult for me to plot the most expeditious route to visit the most Carnegies, unless I buffed up my geocoding skills, so I bruteforced it. So I wander.

I’ve dipped into two more recovery memoirs, this time for individuals who were famous before they were best sellers: Sally Fields In Pieces and Matthew Perry’s Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing. I avoid celebrity memoirs, not because they are uninteresting but because I’m not much interested in celebrity. They are so different in their voices – his, brassy; hers, silk. Their stories of alcoholism bear the lineage of so many others I have heard. As children, they didn’t feel comfortable in their skin. Alcohol made them whole, at first, anyway.

Perry’s favorite song – the one he requested to be played at his funeral – was Peter Gabriel’s “Don’t Give Up,” which he sings with Kate Bush. In my late 20s, I loved that song, from the album So, so I looked it up.

Don’t give up

‘Cause you have friends

Don’t give up

You’re not beaten yet

Don’t give up

I know you can make it good.

Not written by an alcoholic, it’s a helpful message to us. That song reminded me of another of Gabriel’s, “Sledgehammer,” which I hadn’t listened to in years:

I get it right

I kicked the habit

Shed my skin

This is the new stuff

I go dancing in

Good stuff. Thanks, Peter.

Traveling around Indiana has put me into an Our Town mood. Most of the Indiana I’ve been seeing is Grover’s Corners, 2024. Thornton Wilder’s is set in the era 1901-13, yet when I’m off the Main Street, away from the ubiquitous Taco Bells and the still existing Shorty’s Steakhouses, I am transported to the times when front porches were for sitting, not show. Most of the houses are frame, solid if not so much as the rarer brick houses against winter storms and summer sizzle.

These Indiana Our Towns remind of the Fayetteville of my childhood. I feel at home here. Like most modest Indiana towns, it is almost (95 percent) entirely white. Like almost anywhere I travel in the US, I know that my presence is welcomed and my position in the social hierarchy is secure. Minorities are truly minorities here. According to the 2010 census (the most recent posted on Wikipedia) Garrett had 6028 white residents, 28 African Americans, 28 Asian Americans, 26 American Indians or Alaskan Natives, and 176 listed as “other, two or more races, or Pacific Islanders.”

I have been in crowds before where I was the one who stood out. The first word I remember learning when I studied in Japan was “gaijin” (foreigner) which I learned as school children pointed at me with amazement. A couple of years ago I was in a hookah bar in New York, and at some point I noticed that I was the only white person there. The difference is that I’m not in a group that has experienced persistent discrimination. Even when I stood out, I assumed that I did so as a member of the court and not as one of the serfs.

What triggered my Our Town reflections was that the play came to me three times yesterday. It features prominently in the truly wonderful movie Wonder (directed by Steven Chobsky, who wrote The Perks of Being a Wallflower). It was the first play Sally Fields and Matthew Perry acted in. It’s an American classic.

Comments