Day 93, Friday June 7, 2024: Evansville, Indiana to Shelbyville, Kentucky

- Mark Carl Rom

- Jun 17, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jun 21, 2025

Carnegie libraries visited: Rockport, Indiana; Portland, Western, Main, and Crescent Hill branches in Louisville, Kentucky.

Days sober: 351

I ate breakfast on a picnic table behind my hotel this morning. The table had a helpful sign: “Do not clean your fish here and leave their heads on the ground.” The ground, thankfully, was headless.

My internet is superior to that of the Illinois’ state library system. Today, anyway. All the state’s libraries are connected to a central internet provider, and today it’s as dysfunctional as Mary Karr’s family: the entire system is down. Not the Mark R hotspot, however; I’m online.

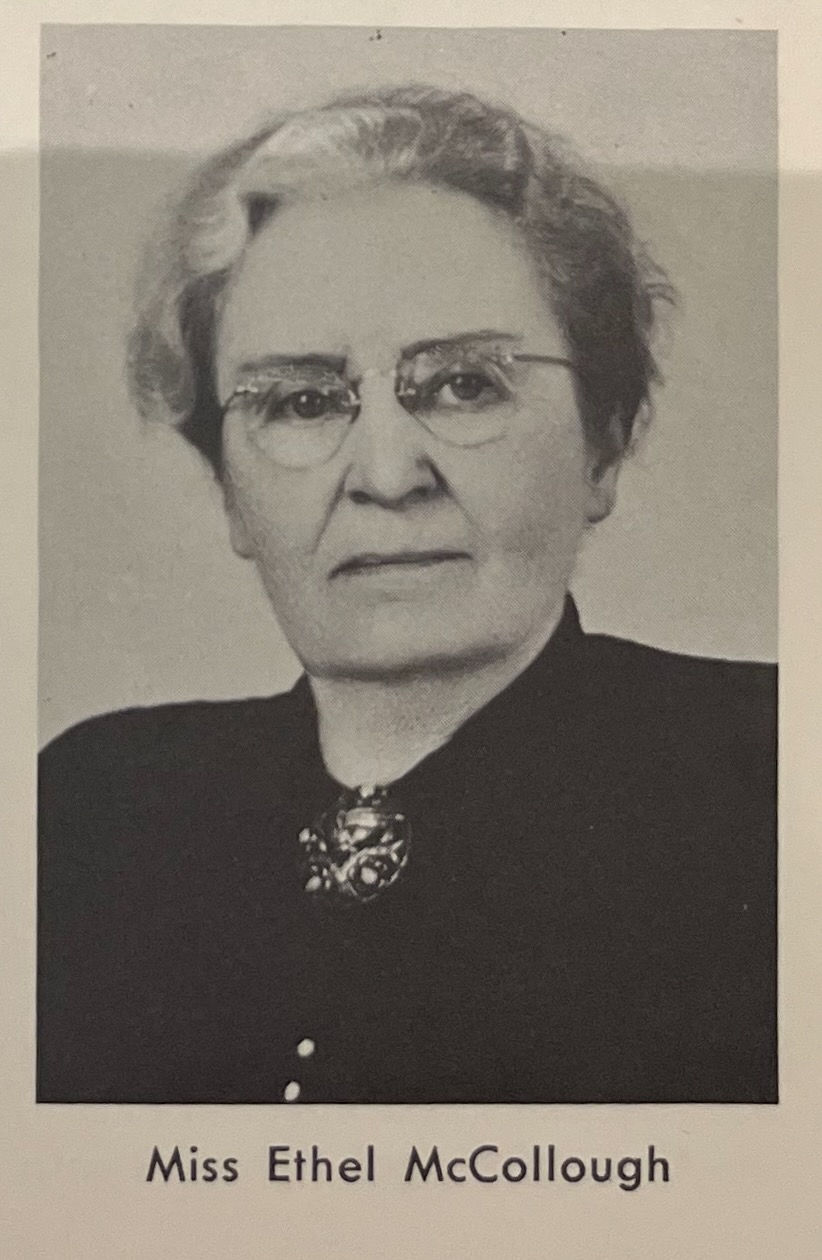

The McCollough Branch of the Evansville, Indiana library system – my first library of the day – is named after Ethel Farquhar McCollough, who served the library system for 35 years between 1911 and 1947, hired at 36 and retired at 71. When I asked about her, Judy and Shannon – librarians at the Evansville Vanderburgh library – gave me the pamphlet “The First Fifty Years: The Evansville Public Library and the Vanderburgh County Public Library,” which included details about her, and much, much, more. I skimmed past the part about the town’s library origins (beginning with a library’s founding in 1848 and culminating with the Carnegie grant to build the East and West branch libraries in 1909), eager to get to the bits about McCullough.

When the newly formed Library Board sought advice on whom to hire as Chief Librarian, Carl H. Millan, the Secretary of the Indiana Library Commission, advised that if there is a choice between “an excellent woman or fairly good man, by all means take the excellent woman.” Ethel, who was the President of the Wisconsin Library Association and an Indiana native, was that woman. When she arrived she inherited two libraries under construction and neither staff nor books. By the time East and West libraries opened in 1913, she had 5527 books and staff.

Born in 1876 in Franklin, Indiana, McCollough attended Franklin College Preparatory School and then stayed in town to attend Franklin College, before she decamped to the New York Library School (the school that was established after Melville Dewey’s school at Columbia University was closed) to earn her bachelor of library science. Returning to Indiana, she served as Librarian in Elwood, Indiana, from 1904 to 1907, where one of her readers was Wendell Wilkie, who went on to become the Republican presidential nominee in 1940). She served a term as Librarian in Superior, Wisconsin and as an instructor at the University of Wisconsin Library School (go Badgers!) Over her career she had numerous professional accomplishments, such as serving as the president of both the Wisconsin and Indiana library associations and editing Stearns Essentials in Library Administration. During World War I, she helped organize libraries on behalf of the ALA War Service Committee for American soldiers serving on the Mexican border.

McCollough was detailed and diligent; she required monthly and annual reports (in duplicate) from each of her departments, and she read them closely, returning with her additions, corrections, and comments. She responded to requests promptly, with “no” a common answer. She, or her assistant, would drop into the various library agencies unannounced for inspections. She opened a competitive apprenticeship program in 1912 – the year she was hired – with the expectation that those enrolled would gain additional training in the library field (at first, the apprentices were unpaid, although by 1915 they earned $1 per day). As the First Fifty Years put it,

Miss McCollough had tremendous energy, a host of ideas, a ready mind and tongue, and complete dedication to the cause of public library service. She established for the Evansville Public Library an enviable national reputation, and deserves most of the credit for the successes of the Library.

When McCollough was hired by Evansville in 1912, the two Carnegie branches were under construction and “there were no books, no staff, and no place to work” except temporary quarters. Before these libraries were even open McCullough asked the Library Board to create a separate branch to serve African Americans. Carnegie provided $10,000 to build the Cherry Branch Library for this purpose. At the time, it was the only public library in Indiana exclusively for Blacks (Indianapolis later built three more). In 1955 it was sold to the Boy Scouts, and the proceeds were used to buy a bookmobile. In 1970 the Cherry Branch was demolished to make way for an addition to a hospital. Except in some faded black and white photos, it exists only in rapidly vanishing memories.

Librarian Shannon wasn’t sure if Blacks were legally prohibited from using the other libraries; she thought they probably were. In 1851 Indiana adopted a Constitution that had prohibited Blacks from moving into the state. In 1866 the state’s Supreme Court invalidated this provision, and it was removed from the constitution in 1881. I was unable to verify whether there were legal prohibitions against Blacks using public libraries, but the fact that separate libraries were (a few times) sought for them suggests that there was a ban.

Hello, Lillian Haydon Childress Hall. Hall was the first African American to graduate from the Indiana state library school, the first professionally trained African American librarian in Indiana, and one of the first hires of the Cherry Branch Library, where she began as an apprentice in 1915. After receiving her degree, she was promoted to become the branch’s librarian. She left that library in 1921 to take a management position in the Indianapolis Public Library's first branch in the Martindale-Brightwood area, an African American neighborhood. After 1927, she served the rest of her career as the chief librarian of the Crispus Attucks High School, retiring after 29 years there.

Beginning in 1913, McCollough opened “deposit stations” (where books were delivered to be checked out) in public schools. The library grew steadily under her guardianship; already by 1913 she had seven staffers, including Assistant Chief Librarian Miss Elsie McKay. In a photograph taken in 1922, McCollough had at least 21 librarians in her charge, including two African Americans: all women. Recognizing that it was, uh, weird to have only branch libraries and no central one, McCullough worked to get one and by 1924 she had succeeded. Because Evansville’s libraries were for Evanville’s residents, McCollough encouraged the library to open its doors wider, and so in 1920 a county-wide tax was levied so all residents of the county could have access to the stacks. She established a bookmobile to bring books to the people who could not come to the library in person. McCollough made it a point to visit libraries in other cities to learn from them and, I would not be surprised, to provide guidance. She retired in 1947 and, when she died in 1950, she was buried in her hometown, Franklin.

From the outside, the Carnegie in Rockport does it right. The main entrance, which faces the county courthouse in the park on the town square, is as fresh as it was on the day it opened in 1919. The ADA compliant entrance, and the new wing to which it opens, is tucked inconspicuously to the side and back. Inside, the historic glamor is unfortunately masked. Acoustic tiles and flat institutional panel lights cover the ceiling. Still, the slightly scarred oak desk, right by the front window, makes me feel as if I could have been one of the original patrons, only now with a laptop.

The stairwell leading from the children’s room to the main reading room in the Rockland Carnegie had pictures of all the library’s head librarians and their terms of service. Anna Bartrim, the original director, served only from February 16, 1916 to August 13, 1919: she died two weeks later. Her successors included:

Jessie Bibbs, 1919-22

Sarah Hill, 1922-27

Clara Thurman, 1927-1930

Mildred Reminick, 1930-40

Katherine Hougland, 1940-51

Emma Casswell, 1951-57 (who like Anna, she also died the same month she stopped serving)

Not identified, 1957-69

Elsie Fay, 1969-77

Beverly Symon, 1977-2013

Sherri Risse, 2013-present

I was surprised by the attenuated tenure of most of them: four Head Librarians in the first ten years? All women? No surprise.

Beverly Symon’s profile caught my eye, as she served for 36 years. When I asked Marie at the front desk about her, saying how often it seemed that I wasn’t able to find out much about such long-serving librarians because they didn’t marry or have children, she replied “Oh, not Beverly. She was married to a police officer and had two kids.”

Oh, you worked with her?

“No, but we attended the same church.” Marie passed me off to Eva in the genealogy section. Eva, with short spiky hair and wearing a blue shirt with the Peanuts character Snoopy asking “Ready to read?” and some other words I couldn’t make out because I didn’t want to stare. Eva dug through the files and slid me a folder of library history to peruse. She thought I might have better luck with Sherri, the Head Librarian, who was eating lunch, and hearing that made my stomach growl because I was not. Sherri, who had started working at the library when she was in high school, before getting a degree in library science and staffing other libraries, informed me, sensibly, that she could not share any information about Symon because she was still alive. Privacy concerns, and all that. She did suggest that I try to look her up in the phone directory, as Symon currently lives somewhere near Indianapolis. No luck.

Comments